I map the passage of time through a series of cycles; knowing only that one exists at its end, knowing its end is near in my growing need to strip my entire life bare. By this I mean, every relationship, every place, every moment spent in a way that feels like sandpaper is a clue into what stays and what goes. The former is only realized after the latter is complete. Or so it was.

Recently, I spent some time wandering the streets of Lisbon during a bout of needing to reorient myself to what is important to me. Answers I seem to only find in far-removed isolation. I do this every few months or so.

This time, however, was my first trip outside of the States alone; my preferred method of travel for its ability to bring you within the closest proximity to your intuition. No guiding force of preconceived notions or familiarity, no conflicting opinions of others, all you have is your gut and your desires. There is no better place to be left alone with these than Lisbon.

Lisbon is a city drenched in poetry and an aureate light you feel you can just about reach from atop its winding hills. A city full of answers that find you before the questions are even posed.

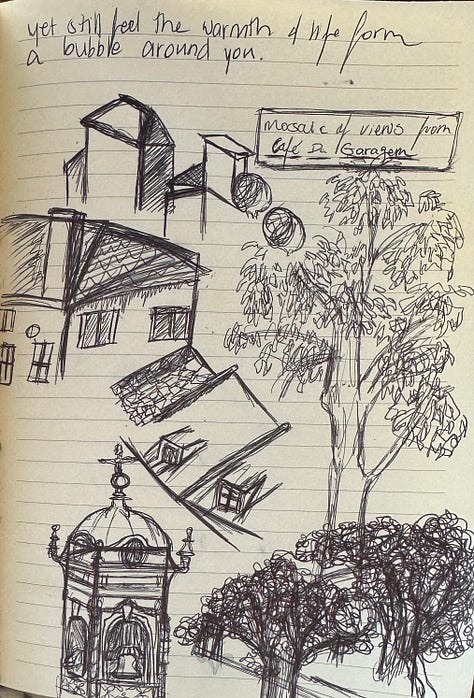

The characteristic cobblestone streets, buildings covered in hand-painted cerulean blue tile, and linens blowing in the early Spring wind are just as breathtaking in person. Well in touch with its Moorish influence, it remains a mosaic of art, life, love, poetry, and pleasure. But what made Lisbon the experience it was for me was not only the fresh seafood, architecture, or endless wine, but the feeling that you can be left completely alone to wander through the streets in peace; in safety. A city that feels like it is actively encasing you in a protective bubble so you can embrace child-like exploration. A freedom to fully exist that I haven’t felt since, well, I was a child.

Maybe not even then.

I spent days climbing [unimaginably steep] hills and listening in to the world of language around me. After a while, the German, French, and Portuguese voices all blurred together into a cacophony of expression. During meals, I— slinked into a back corner of each cafe with pen and journal as dinner companions— tried to decipher the stories of people around me based on their laughter and cadence alone. By the third day of this, I grew tired of not understanding. I found comfort in the familiarity of the birds and their songs.

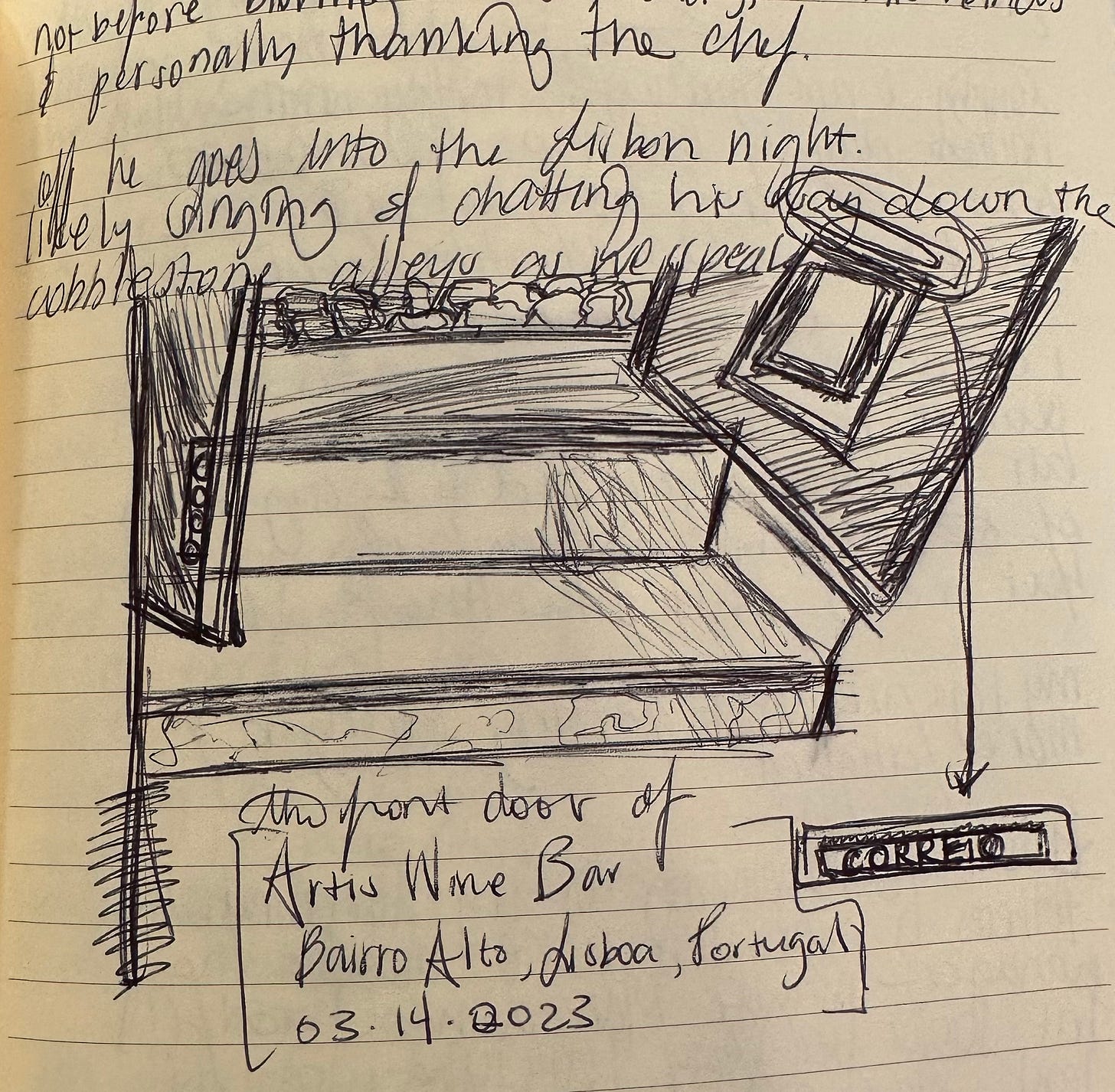

As the light waned on an afternoon spent in Alfama, one of the oldest neighborhoods in the city, I felt the setting sun with the sounds of Fado. Fado is traditional Portuguese music rooted in saudade: a feeling of longing, nostalgia. My limited understanding of Portuguese culture grasps that it is full of this sense of yearning and the peculiar celebration of it. A lovely man named João explained saudade as the soul of Lisbon. My people.

The voices of acapella Fado singers fill the rooms of each cafe and overflow onto the streets. Many walk past, not paying particular mind to the origin of this music but becoming noticeably lighter as they flow through the corridor and on with their days. As if they are suddenly afflicted with something far bigger than themselves; a reminder of the depth life carves out for us if we’re open to it.

I spent all of my days in silent observation of these small moments. The microexpressions of strangers, the cracks in cobblestone that bloomed with moss, the way the light slowly drained from the alleyways as the day moved along.

You don’t come back from that experience unchanged. Not because something there was born from you that never was, but in the sense that the city fractures you into all the selves you already are.

One rainy afternoon, I found myself seeking refuge inside Casa Fernando Pessoa; a renovated apartment complex on Rue Coehlo da Rocha that once housed the titular poet and has since been transformed to commemorate his life [or, in this case, many lives]. Fernando Pessoa was a Portuguese poet that lived from 1888-1935. Born in Lisbon, he and his family moved to Cape Town, South Africa following his father’s death, where he became a decorated essayist for works written primarily in English. In his early 20s, he returned to Lisbon, where he would spend the rest of his life.

The museum is brilliantly curated– including 4 floors of discovery in which you are instructed towards an elevator destined for the top floor. On this level, you are introduced to Pessoa’s heteronyms— the facet of his writing that made me feel the most connected to a poet I, hours earlier, had no idea ever lived.

Unlike a pseudonym or alias, Pessoa’s heteronyms were entire people unto themselves with thought-out personalities, histories, and even astrological charts that were painstakingly planned to represent each of the four elements: earth, fire, water, and, his own, air (our Gemini king). They each authored and signed their works; had styles and tones influenced by their unique life experiences. Each used the hands of Pessoa to write but had fractured minds to draw inspiration.

Pessoa did not have a multiple personality disorder or an affinity towards hallucinogens (as modern society would likely categorize him), but rather an understanding that reality is only as real as the stories and performances we make of it. In this sense, all of his heteronyms were just as real as himself.

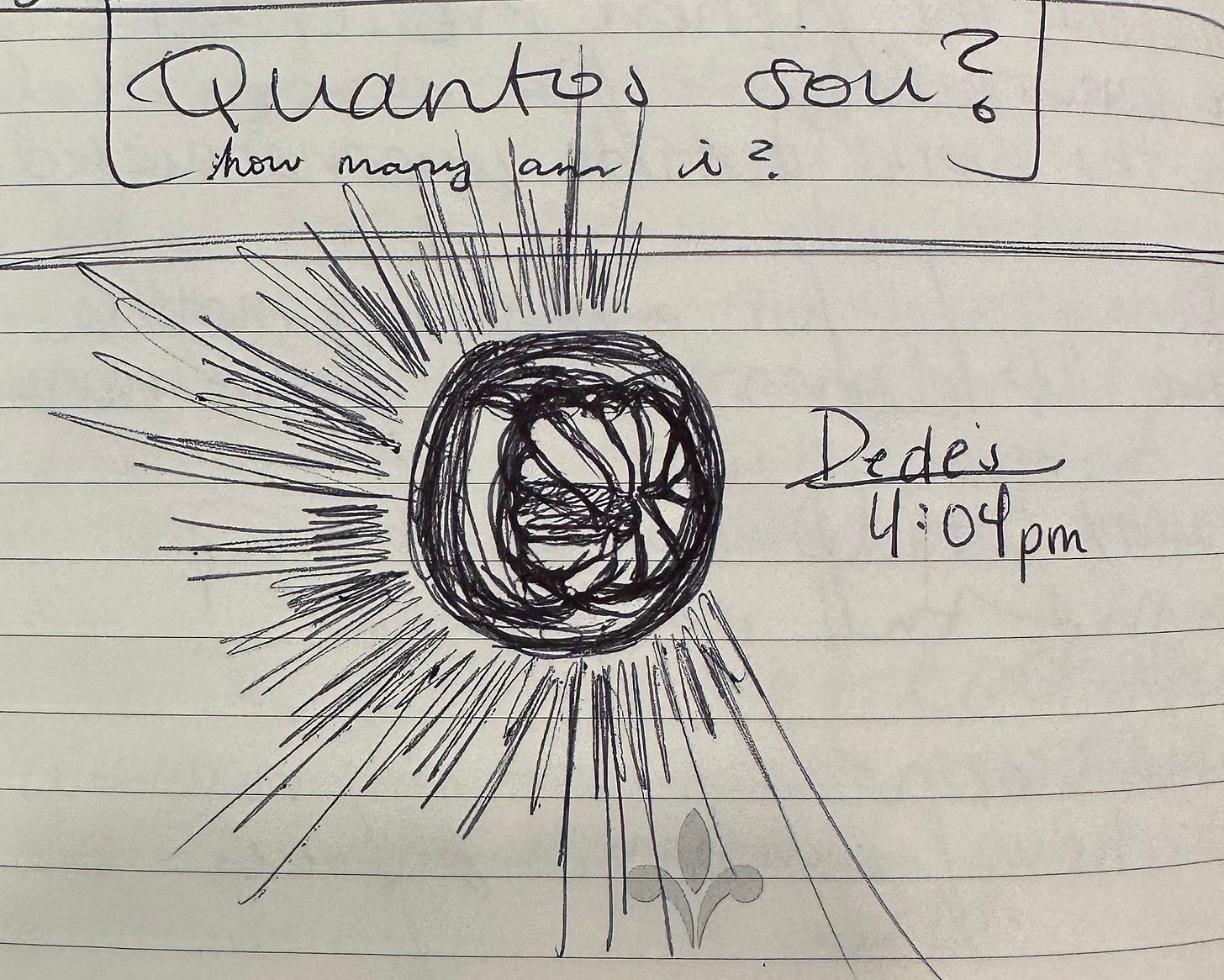

Also on this floor was an installation of a mirrored room that allowed you to see yourself multiple times over– to stand in communion with them. On a blank wall hangs a sign that reads

Quantos sou? (how many am i?).

I’ve been thinking about this room, this poet, and this question from that moment on.

How many am I?

How many iterations of self can one body contain? How much of me can this one life stand to hold?

Cycles– what were once a necessary shedding, a killing off of one version in favor of the other, have now led to the realization that:

A death of self is not a death but a gathering; a making of space.

Death can encompass a rebirth and reincarnation in an Eastern philosophical sense, but also in a rooted, continuation of lineage, of dreams, of desires, of pains. A knowing that every version of me contains a central self that has survived through each cycle of death. An even more central self has survived through generations of cycles of death. I am as much as my own as I am a manifestation of the women who lived and loved so that I could be here; so that I could be a lived continuation of their ever-present life.

This, as with most things, is true for language itself.

In an essay in The Paris Review– Every Poem has Ancestors, indigenous author N. Scott Momaday says,

A poem exists because it says: ‘I am the voice of the poet or what is moving through time, place, and event; I am sound sense and words; I am made of all this; and though I may not know where I am going, I will show you, and we will sing together.’

I talk a lot about the liminal, the space between. How my existence here feels most potent; how life takes more meaning when cast in suspension. Coincidentally, Pessoa wrote about this, too, saying, “I’m the gap between what I’d like to be and what others have made of me. . . . That’s me. Period.” Period!!!

On the last floor of Casa Fernando Pessoa, you find his personal library. A bookshelf full of metaphysics, mathematics, philosophy, poetry, social change— Shakespeare, Baudelaire, Whitman. You get to know someone most intimately through the words they keep close by. And here I was, face to face with a lifetime collection of words that influenced and shaped a mind. Surreal.

In the room over was a vast table littered with Pessoa’s own words from The Book of Disquiet on moveable, clear, acrylic tiles. This was meant to simulate the interchangeability and arbitrary nature of the way the book was constructed; from a collection of papers found stacked in a trunk in Pessoa’s bedroom, scholars pieced together his thoughts how they saw fit post-mortem. Painted on the wall above the table reads

“Algures no labirinto do que realmente sou – somewhere in the maze of who I really am”.

I spent an hour in this room reading, reflecting, and playing this game of disquiet.

Each movement of a tile creates new meaning; endless possibilities to formulate the thoughts of this man without ever knowing how close to the truth you’ll get. But the point of the game is not truth-seeking, it is meaning-making in the context of your own life, thoughts, and understandings at that moment. Each movement is a death of the meaning that just was; a simultaneous birth of the new meaning that is. A meaning that awaits an inevitable death and rebirth infinite times over.

Life is a constant experience with death. It is taking these fractured ideas of self and reforming and reconstructing them into something grander each morning. How, at the end of our life, we’ll do the same once more before passing off this task to all who knew the collection of you. How the story will shift and meld and find new life in those your life had touched. How these stories, and your life too, will never cease to exist through and within the fabric of the life that remains.

Because the story is not yours alone. You are not yours alone. Your lives and deaths, and the lives and deaths of those around you, are merely a continuation. A cycle in which you may not know where you are going, but life will show you and you will sing together.

My stories of Lisbon, of the time I spent there, will change each time I retell them. The memories I have—destined for the same. I’d like to think that they each contain a central tendency rooted in how I felt during.

But the Lisbon I knew for that week also died, in a way, the moment I left. I will never experience it the same way again (and I WILL be experiencing it again and again and again).

I write this out of a desire to commemorate this one, concentrated experience. To immortalize it. Thinking of immortality as the remnants of life;

What remains after death?

What remains are the lessons, the questions, the desires. What remains are the fado and birdsong. What remains are the stories we tell.

Something central. Something from before. Something that has yet to happen. How you felt. The look of their hands; the way they held you in them. A whistle. A name. A gentle push. A comfort. A long-lasting, painful grief.

A love. A love. A love.